NOTE: Lawyers representing Omar Khadr note that the portions of this article dealing with Omar’s life before capture come only from military, government and press accounts, particularly the depictions of the Khadr family. They do agree with the depiction of his torture and other mistreatment, however, which came to them directly from credible, unclassified statements made by their client to them, and made part of the court records in this case. The July, 2005 decision to enjoin Mr. Khadr’s future torture, decided by a federal district court in Washington, DC (opinion attached here), found that, even if true, the allegations of mistreatment were not recent enough to justify the court’s intervention. The court also refused to require the government to give notice prior to rendering Mr. Khadr to another country, even where there was evidence that the rendition was to a country known to torture. No appeal was taken from that decision. (Richard Wilson, Professor of Law, personal communication, April 2007).

Rolling Stone | August 24, 2006 Jeff Tietz

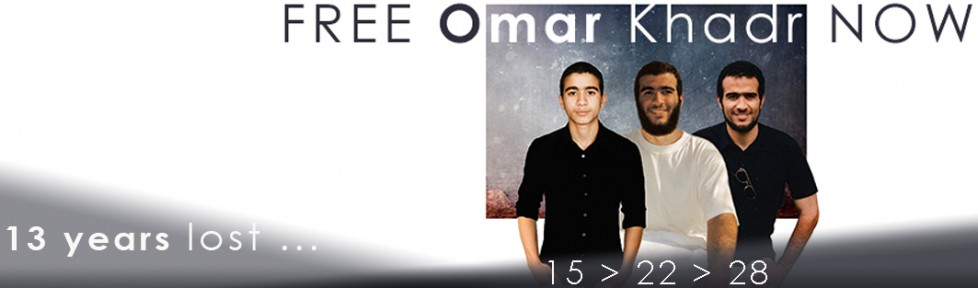

He was a child of jihad, a teenage soldier in bin Laden’s army. Captured on the battlefield when he was only fifteen, he has been held at Guantanamo Bay for the past four years — subjected to unspeakable abuse sanctioned by the president himself.

In July 2002, a Special Forces unit in southeast Afghanistan received intelligence that a group of Al Qaeda fighters was operating out of a mud-brick compound in Ab Khail, a small hill town near the Pakistani border. The Taliban regime had fallen seven months earlier, but the rough border regions had not yet been secured. When the soldiers arrived at the compound, they looked through a crack in the door and saw five men armed with assault rifles sitting inside. The soldiers called for the men to surrender. The men refused. The soldiers sent Pashto translators into the compound to negotiate. The men promptly slaughtered the translators. The American soldiers called in air support and laid siege to the compound, bombing and strafing it until it was flat and silent. They walked into the ruins. They had not gotten far when a wounded fighter, concealed behind a broken wall, threw a grenade, killing Special Forces Sgt. Christopher Speer. The soldiers immediately shot the fighter three times in the chest, and he collapsed.

When the soldiers got close, they saw that he was just a boy. Fifteen years old and slightly built, he could have passed for thirteen. He was bleeding heavily from his wounds, but he was — unbelievably — alive. The soldiers stood over him.

“Kill me,” he murmured, in fluent English. “Please, just kill me.”

His name was Omar Khadr. Born into a fundamentalist Muslim family in Toronto, he had been prepared for jihad since he was a small boy. His parents, who were Egyptian and Palestinian, had raised him to believe that religious martyrdom was the highest achievement he could aspire to. In the Khadr family, suicide bombers were spoken of with great respect. According to U.S intelligence, Omar’s father used charities as front groups to raise and launder money for Al Qaeda. Omar’s formal military training — bombmaking, assault-rifle marksmanship, combat tactics — before he turned twelve. For nearly a year before the Ab Khail siege, according to the U.S. government, Omar and his father and brothers had fought with the Taliban against American and Northern Alliance forces in Afghanistan. Before that, they had been living in Jalalabad, with Osama bin Laden. Omar spent much of his adolescence in Al Qaeda compounds.

At Ab Khail, a sergeant later said, every U.S. soldier who walked by Omar longed to put a bullet in his head. But an American medic, working near the corpse of Sgt. Speer, saved Omar’s life, and he was taken to a hospital at Bagram Air Base with a bullet-split chest and serious shrapnel wounds to the head and eye. U.S. intelligence officers began interrogating him as soon as he regained consciousness. At that moment, Omar entered the extralegal archipelago of torture chambers and detention cells that the Bush administration has erected to prosecute its War on Terror. He has remained there ever since.

At Bagram, he was repeatedly brought into interrogation rooms on stretchers, in great pain. Pain medication was withheld, apparently to induce cooperation. He was ordered to clean floors on his hands and knees while his wounds were still wet. When he could walk again, he was forced to stand for hours at a time with his hands tied above a door frame. Interrogators put a bag over his head and held him still while attack dogs leapt at his chest. Sometimes he was kept chained in an interrogation room for so long he urinated on himself.

After the invasion of Afghanistan, President Bush decided, in violation of the Geneva Convention, that any adolescent apprehended by U.S. forces could be treated as an adult at age sixteen. The problem with treating teenage prisoners as adults, whatever their crimes, is that teenagers are especially

Before boarding a C-130 transport to Guantanamo, Omar was dressed in an orange jumpsuit and hog-chained: shackled hand and foot, a waist chain cinching his hands to his stomach, another chain connecting the shackles on his hands to those on his feet. At both wrist and ankle, the shackles bit. The cuffs permanently scarred many prisoners on the flight, causing them to lose feeling in their limbs for several days or weeks afterward. Hooded and kneeling on the tarmac with the other prisoners, Omar waited for many hours. His knees sent intensifying pain up into his body and then went numb.

Just before he got on the plane, Omar was forced into sensory-deprivation gear that the military uses to disorient prisoners prior to interrogation. The guards pulled black thermal mittens onto Omar’s hands and taped them hard at the wrists. They pulled opaque goggles over his eyes and placed soundproof earphones over his ears. They put a deodorizing mask over his mouth and nose. They bolted him, fully trussed, to a backless bench. Whichever limbs hadn’t already lost sensation from the cuffs lost sensation from the high-altitude cold during the flight, which took fifteen hours. “There was points I wished to God that one of these MPs would go crazy and then shoot me,” recalled one of the hundreds of detainees who have made the trip. “It was the only time in my life that I really wished for a bullet.”

At Guantanamo, Omar was led, his senses still blocked, onto a bus that took the prisoners to a ferry dock. Some of the buses didn’t have seats, and the prisoners usually sat cross-legged on the floor. Guards often lifted the prisoners’ earphones, told them not to move, and when they moved — helplessly, with the motion of the bus, like bowling pins — started kicking them. The repeated blows often left detainees unable to walk for weeks.

After the ferry ride, Omar was evaluated at a base hospital. “Welcome to Israel,” someone told him. Then he was locked in a steel cage eight feet long and six feet wide. Because the cage had a sink and squat-toilet and the bed was welded to the floor, the open floor space was comparable to that of a small walk-in closet. The cages had been hurriedly constructed from steel mesh and transoceanic shipping containers. Giant banana rats ran freely through the cells and across the roofs and shit everywhere: on beds, on sinks, on Korans. Prisoners were allowed only one five-minute shower each week; the cellblocks stood in a perpetual stench.

Omar’s arrival at Guantanamo in October 2002 coincided with a fundamental turn in the administration’s War on Terror. Within weeks of his arrival, at the authorization of President Bush, interrogators at the detention facility began using starkly inhumane techniques. Before Omar Khadr had even started to assimilate the wondrous horrors of Guantanamo Bay, his captors began to torture him.

Ahmed said Khadr, Omar’s father, always said he did not want to die in bed. He wanted to be killed. When his children were very young, he told them, “If you love me, pray that I will get martyred.” Three times he asked Omar’s older brother Abdurahman to become a suicide bomber. It would bring honor to the family, he said. Abdurahman declined. Later, when Ahmed sensed that Abdurahman’s faith was weakening, he told him, “If you ever betray Islam, I will be the one to kill you.”

Omar and his brothers attended madrassahs and Islamic schools. His mother and two older sisters covered their bodies and completely veiled their faces. At home, the Khadr children were warned that the purity of Islam was being compromised, from within and without. The quest to repurify it diminished to insignificance everything else in life. Purity was the simple measure by which good and evil were distinguished, and the means of destroying evil were equally simple. The Khadr children were raised to serve a purpose. Their fealty was sounded every day.

In 1988, when Omar was two, the Khadrs left Toronto for Peshawar, Pakistan, so Ahmed could take a job with a charity called Human Concern International. In those days, Peshawar was an operational base for Islamist insurgents fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan. Osama bin Laden had gone there to recruit, fund and train mujahedeen. Intelligence sources claim that many of the orphans and refugees aided by Khadr later became fundamentalist guerrillas under the guidance of bin Laden.

In 1992, not long after Omar had begun his studies at a madrassah in Peshawar, Ahmed nearly died after stepping on a land mine in Logar Province, Afghanistan. (Intelligence sources say he had gone there to fight with predecessors of the Taliban in the Afghan civil war.) Ahmed was evacuated to a hospital in Toronto, and the rest of the family returned to Canada with him. It would take him two years to recover.

Of the Khadr children, Omar was the closest to his father. He was seven when Ahmed got hurt. It was hard to keep him away from his father’s bedside. In Toronto, he proved to be one of those unusual children who take it upon themselves to care for their families — he seemed to want to hold his father’s place until Ahmed recovered. “He was always there for us,” his sister Zaynab recalled later. When someone wasn’t feeling well, Omar would always bring them the comfort food they liked best. He was hypersensitive to tension in the family and instinctively dispelled it: He often did an impersonation of Captain Haddock, the spluttering character from the Belgian comic-book series Tintin, which Omar loved: “Buh-buh-billions of bl-bl-blistering bl-bl-blue barnacles!” he would say, or “Ten thousand thuh-thuh-thundering typhoons!” It always broke everybody up.

Donations collected at the Khadrs’ mosque paid the rent while Ahmed was in the hospital. The Isna Islamic School waived tuition for the Khadr children. At school, Omar did well in everything. He began memorizing the Koran, in Arabic, at age seven. He seemed to know that his successes could counterbalance the underachievements of his brothers. On Abdurahman’s report card, his Islamic-studies teacher wrote, “May Allah help him.” Omar’s teachers made it clear that they were grateful to have him in their classes. “He was very smart, very eager and very polite,” one recalled.

As soon as Ahmed was well enough to walk with a four-pointed cane, he moved the family back to Peshawar and resumed working for Human Concern International. Not long after they arrived, when Omar was nine, terrorists led by Ayman al-Zawahiri suicide-bombed the Egyptian embassy in Islamabad. According to Pakistani intelligence, much of al-Zawahiri’s operational funding had passed through Human Concern International. One of the vehicles used in the attack had been purchased by a Sudanese man living with the Khadrs. The entire Khadr family was detained, their compound was raided, and Ahmed was imprisoned and tortured.

When the family was finally allowed to visit Ahmed in prison, they found a crippled old man primitively confined alongside murderers and armed robbers. Omar seemed unable to recover from this sight. Ahmed, maintaining his innocence, went on a hunger strike and was hospitalized. Omar spent every night at the hospital, curled up on the concrete floor beneath his father’s bed.

Omar had not reached the age of reason; his nine-year-old imagination could not yet accommodate the world’s layers. But he had been trained, with special care, to divide the universe into the province of righteous work and the forces arrayed against it. Twice now he had watched his father nearly die in the service of righteousness. The forces Omar Khadr had been warned against must have seemed, from beneath his father’s second hospital bed, very real: omnipresent and irrational, destroying the sacred for its very sanctity. If Omar’s kind disposition seemed to dissent from the hardness of his family’s beliefs, then witnessing his father’s suffering ended it. Ahmed’s identity subsumed Omar’s own; the son accepted the price and necessity of the father’s cause. Omar did not lose his uncommon altruistic compassion, but he acquired, unavoidably, a fixed fervency he seemed ready to act on. The Toronto imam who had known him when he was seven said Omar’s experience in Pakistan left him “radicalized.”

After four months in prison, Ahmed Said Khadr was released at the request of the Canadian government. He moved his family to Jalalabad, Afghanistan, to live with Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden and his many wives and children occupied a large dirt-wattle compound surrounded by military training camps. The Khadr family denies being part of Al Qaeda, but the U.S. government says that Omar was soon sent to join his older brothers, Abdullah and Abdurahman, at a military camp outside the town of Khalden. The camp provided instructional units on handguns, sniper tactics and marksmanship, assault rifles, bombmaking and combat tactics.

Life in the Jalalabad compound was spare. Bin Laden forbade ice and electricity. He wanted people to know how to live with nothing. Abdurahman later described him as a regular guy who liked volleyball and horse racing. “He had financial issues, issues with his kids,” Abdurahman said. “‘The kids aren’t listening. The kids aren’t doing this and that.'” Bin Laden’s children drank Coke whenever they could, despite his ban on American products. To get them to memorize the Koran, bin Laden promised to buy them horses.

In 1998, when Al Qaeda members suicide-bombed the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 220 people and wounding 4,000, everyone in the Jalalabad compound celebrated. A lot of free juice was handed out. People joked that they should carry out more operations — they’d get free juice all the time. The celebration ended when the Americans retaliated with cruise missiles, destroying buildings and killing and wounding a dozen people. For Omar, the attack reinforced, as nothing else had, his belief that the enemy was real. Omar was fourteen on September 11th. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon created an uproar of rejoicing in the camps, but everyone knew that serious American reprisals were imminent, and the compounds were abandoned. Abdurahman, who had become deeply disillusioned with Al Qaeda’s killing of civilians, defected to Kabul, where he was taken prisoner by the Northern Alliance and handed over to the CIA. According to the U.S. government, Omar followed his father into the mountains, where they soon began fighting for Al Qaeda.

Whatever his indoctrination at that moment, Omar would still have been recognizable to the people who had known him as a boy in Toronto. “Omar is our mother and our father, our sister and our brother,” Ahmed wrote in a letter to Zaynab. “He does everything for us. He cooks our meals and does our laundry. Sometimes, I ask your mother: Are you sure he’s ours? He’s too good to be ours.”

A few months after Omar Khadr arrived at Guantanamo Bay, he was awakened by a guard around midnight. “Get up,” the guard said. “You have a reservation.” “Reservation” is the commonly used term at Gitmo for interrogation.

In the interrogation room, Omar’s interviewer grew displeased with his level of cooperation. He summoned several MPs, who chained Omar tightly to an eye bolt in the center of the floor. Omar’s hands and feet were shackled together; the eye bolt held him at the point where his hands and feet met. Fetally positioned, he was left alone for half an hour.

Upon their return, the MPs uncuffed Omar’s arms, pulled them behind his back and recuffed them to his legs, straining them badly at their sockets. At the junction of his arms and legs he was again bolted to the floor and left alone. The degree of pain a human body experiences in this particular “stress position” can quickly lead to delirium, and ultimately to unconsciousness. Before that happened, the MPs returned, forced Omar onto his knees, and cuffed his wrists and ankles together behind his back. This made his body into a kind of bow, his torso convex and rigid, right at the limit of its flexibility. The force of his cuffed wrists straining upward against his cuffed ankles drove his kneecaps into the concrete floor. The guards left.

An hour or two later they came back, checked the tautness of his chains and pushed him over on his stomach. Transfixed in his bonds, Omar toppled like a figurine. Again they left. Many hours had passed since Omar had been taken from his cell. He urinated on himself and on the floor. The MPs returned, mocked him for a while and then poured pine-oil solvent all over his body. Without altering his chains, they began dragging him by his feet through the mixture of urine and pine oil. Because his body had been so tightened, the new motion racked it. The MPs swung him around and around, the piss and solvent washing up into his face. The idea was to use him as a human mop. When the MPs felt they’d successfully pretended to soak up the liquid with his body, they uncuffed him and carried him back to his cell. He was not allowed a change of clothes for two days.

The design of Omar Khadr’s life at Guantanamo Bay apparently began as a theory in the minds of Air Force researchers. After the Korean War, the Air Force created a program called SERE — Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape — to help captured pilots resist interrogation. SERE’s founders wanted to know what kind of torture was most destructive to the human psyche so that they could train pilots to withstand it. In experiments, they held subjects in dummy POW camps and had them starved, stripped naked and partially drowned. Administrators carefully noted the subjects’ reactions, often measuring the levels of stress hormones in their blood.

The most effective form of torture turned out to have two components. The first is pain and harm delivered in unpredictable, sometimes illusory environments — an absolute denial of physical comfort and spatial-temporal orientation. The second is a removal of the inner comfort of identity — achieved by artfully humiliating people and coercing them to commit offenses against their own religion, dignity and morality, until they become unrecognizable to and ashamed of themselves.

SERE scientists came up with a variety of stress-torture techniques: sleep deprivation, sexual mortification, religious desecration, hooding, waterboarding. In SERE theory, the techniques are be used in concert and continuously — coercive interrogation should become a life experience. This is Guantanamo Bay: To be held there is, per se, to be tortured. Behavioral scientists reportedly manage every aspect of detainees’ lives. In one case, a psychologist told guards to limit a detainee to seven squares of toilet paper a day.

While he was at Guantanamo, Omar was beaten in the head, nearly suffocated, threatened with having his clothes taken indefinitely and, as at Bagram, lunged at by attack dogs while wearing a bag over his head. “Your life is in my hands,” an intelligence officer told him during an interrogation in the spring of 2003. During the questioning, Omar gave an answer the interrogator did not like. He spat in Omar’s face, tore out some of his hair and threatened to send him to Israel, Egypt, Jordan or Syria — places where they tortured people without constraints: very slowly, analytically removing body parts. The Egyptians, the interrogator told Omar, would hand him to Askri raqm tisa — Soldier Number Nine. Soldier Number Nine, the interrogator explained, was a guard who specialized in raping prisoners.

Omar’s chair was removed. Because his hands and ankles were shackled, he fell to the floor. His interrogator told him to get up. Standing up was hard, because he could not use his hands. When he did, his interrogator told him to sit down again. When he sat, the interrogator told him to stand again. He refused. The interrogator called two guards into the room, who grabbed Omar by the neck and arms, lifted him into the air and dropped him onto the floor. The interrogator told them to do it again — and again and again and again. Then he said he was locking Omar’s case file in a safe: Omar would spend the rest of his life in a cell at Guantanamo Bay.

Several weeks later, a man who claimed to be Afghan interrogated Omar. He wore an American flag on his uniform pants. He said his name was Izmarai — “lion” — and he spoke in Farsi and occasionally in Pashto and English. Izmarai said a new prison was under construction in Afghanistan for uncooperative Guantanamo detainees. “In Afghanistan,” Izmarai said, “they like small boys.” He pulled out a photograph of Omar and wrote on it, in Pashto, “This detainee must be transferred to Bagram.”

Omar was taken from his chair and short-shackled to an eye bolt in the floor, his hands behind his knees. He was left that way for six hours. On March 31st, 2003, Omar’s security level was downgraded to “Level Four, with isolation.” Everything in his cell was taken, and he spent a month without human contact in a windowless box kept at the approximate temperature of a refrigerator.

When he was not being tortured or held in isolation, Omar spent virtually every waking minute of his captivity at Guantanamo alone in his cell, first in a facility called Camp Delta and then in one called Camp V. His left eye, the one injured at Ab Khail, had gone blind and was immobile. Except for a Koran, there was nothing in Omar’s cells to occupy his mind. During his first year and a half at Guantanamo, he was permitted to exercise only twice a week for fifteen minutes, in a cage slightly larger than his own. Conversation between cells was possible, but prisoners had become so unstable and fearful of one another that they tended not to say much; there were no friendships. Omar tried to talk to his guards, about anything, but they were unresponsive. They often covered their nameplates with tape before entering detention facilities.

As Guantanamo was imposing heavy stagnation on Omar, it was also instilling in him an abiding sense of vulnerability and disequilibrium. The call to prayer was usually played five times a day, but sometimes it changed, or stopped. Exercise could come at any time of the day or night. If the guards woke you at 3:30 a.m. and you didn’t present yourself quickly enough to please them, you didn’t get to exercise. The timing and character of interrogations followed no pattern. Sometimes prisoners were woken up and moved from cell to cell for half the night for no apparent reason. This tactic was so common it became known among guards as “the frequent-flier program.”

Meal portions were usually small enough to keep the prisoners in a state of low-grade hunger. Several times Omar found powder or partially dissolved tablets in the plastic glass he got with his food. The drugs produced dizziness, sleepiness or hyperalertness. Tasteless and invisible, they were not detectable beforehand. Omar was never told what they were or why he had been drugged. Once, when he was being transferred, Omar learned that his brother Abdurahman was in an adjacent prison yard. Abdurahman, forced by the CIA to choose between life imprisonment and cooperation, had chosen the latter. Omar had no idea that his brother was in Guantanamo to spy on detainees.

“How are you? How are you?” Abdurahman yelled in Arabic.

According to Abdurahman, Omar told him to stick to the story the family had agreed upon — the Khadrs did charity work and knew nothing of Al Qaeda.

“But how is your health?” Abdurahman yelled.

“It’s OK,” Omar yelled back. “I’m just losing my left eye and all. They don’t want to operate on it.”

It was the only time they encountered one another. Guards and interrogators continually reminded Omar that no one in the world knew where he was. No one would know if they decided to kill him. He heard gunshots. He heard the sounds other prisoners made when they were dragged back from interrogation rooms. Around the time of Omar’s arrival, detainees watched as guards rushed into the cell of a prisoner named Jumah Al-Dousari and began kicking him in the stomach and bashing his head against the floor. “When they took him out,” one detainee later reported, “they hosed the cell down and the water ran red with blood.” It was the kind of beating Omar witnessed repeatedly.

In July 2004, when Omar was seventeen, he was moved to Camp V. In his new cell the fluorescent ceiling lights stayed on twenty-four hours a day. Sometimes he went for weeks without seeing daylight. His cell was kept cold; Omar spent a lot of his time trying to stay warm: balling himself up, covering his extremities to the extent it was possible, making the best use of his blanket and mattress pad when they hadn’t been confiscated. His metal cot was a problem: It briskly gave away his body heat.

After a day in his Camp V cell, Omar had nothing more to see, touch, taste, hear or smell. He was accompanied only by his own disordered thoughts. He tried to sleep the time away, but the cold was inimical to sleep, and the incessant lighting had divested him of his feel for night and day. Over the course of any given month, Omar did not know whether he would get to see the sun, have a conversation with another human being or be allowed to wear clothes. For the past four years, Guantanamo has held him dead-still in the vacuum of his cell without ever allowing him to come to rest. The institution has made it clear to him that this will remain, for untold years, the form of his life.

One of the chief mental defenses against harsh imprisonment is durable perspective; sanity requires a steady identity. But identity in adolescence is precarious by nature: Teenagers change their identities and beliefs all the time, and they cannot develop a secure perspective in the isolation of captivity. To figure out the world, teenagers have to be in it. For adolescents like Omar Khadr, who have already experienced radical trauma, the characteristic symptoms of months or years of harsh imprisonment — paranoid delusions, suicidal tendencies, hallucinatory psychoses — can become irreversible.

Soon after Omar arrived at Guantanamo, he began exhibiting the kinds of disassociative symptoms most adolescent psychiatrists would have expected. He was startled to the point of disorientation by small changes in his surroundings. He had fainting spells. He cried frequently. When he heard gunshots at Camp Delta, he had a vision of helicopter gunships descending on him, and these kinds of enclosing flashbacks came repeatedly, as did nightmares about the Ab Khail firefight, in which he felt, with phenomenal verisimilitude, bullets piercing his chest. His appetite diminished; he took on the appearance of the permanently malnourished. He entered what clinicians call a state of hypervigilance: He started thinking he might be attacked at any time — without reason, his heart rate would jump, and he would sweat and hyperventilate. He began hearing sounds — screams, bombs, things he could not identify — when the cellblock was silent. Every week or so, a self-generated rage possessed him — an experience wholly foreign to his character. For long periods he felt no emotion at all. He started blaming himself for the things that had happened to him; he became deeply ashamed of what he had suffered. He developed a pronounced twitch on the left side of his face, of which he remained unaware.

As with every other detainee at Guantanamo, Omar’s future became a vacancy upon arrival, and his imagination quickly lost the ability to fill it. There were no conditions for release: The Bush administration had suspended all rules of judicial review and due process. The human mind has tools for dealing with extreme physical and emotional stress, but it is not equipped to manage purgatorial limbo. In every POW camp in history there has been an easily imagined endpoint: the end of the war. In the Soviet gulag, there were charges and trials and sentences, however fraudulent. The machinery was visible. If you weren’t worked to death, you got out. At Guantanamo, what detainee after detainee has said — what study after study has shown — is that insanity and suicidal impulses inevitably accompany the kind of futurelessness Gitmo imposes on its inmates. In June, three detainees hung themselves in their cells, and more than forty others have attempted suicide since 2003. The quantity of such self-destruction, in circumstances so carefully designed to prevent it, indicates a suffusing despair unimaginable outside the gates of the base. Even if all the detainees were released today and received immediate psychological treatment, a great majority would be psychologically impaired for the rest of their lives.

Omar thought earnestly about killing himself. In January 2003, four months after he arrived, his guards were sufficiently worried about his suicidal disposition to confiscate his possessions. Psychosis was all around him. During the fall of 2004, Omar watched an Arab orthopedist named Ayman go insane. Over a period of months, Dr. Ayman became entirely mute, except for an occasional scream and a single question, asked of no one in particular: “Who is a woman here?”

Several medical experts have reviewed the results of two mental-status exams administered to Omar. All concurred in their interpretations. Dr. Eric Trupin, who has written extensively on the effects of incarceration on adolescents, concluded that Omar has been traumatized and tortured to a degree that is, in Trupin’s considerable experience, remarkable.

“The impact of these harsh interrogation techniques on an adolescent such as O.K., who also has been isolated for almost three years, is potentially catastrophic to his future development,” Trupin stated in his report. “Long-term consequences of harsh interrogation techniques are both more pronounced for adolescents and more difficult to remediate or treat even after such interrogations are discontinued, particularly if the victim is uncertain as to whether they will resume. It is my opinion, to a reasonable scientific certainty, that O.K.’s continued subjection to the threat of physical and mental abuse places him at significant risk for future psychiatric deterioration, which may include irreversible psychiatric symptoms and disorders, such as a psychosis with treatment-resistant hallucinations, paranoid delusions and persistent self-harming attempts.”

To see their client Omar Khadr at Guantanamo Bay, Muneer Ahmad and Rick Wilson have to take a chartered single-prop plane from Miami to the base. It takes four hours to circumnavigate Cuban airspace. The bay itself is uncommonly beautiful. It is horseshoe-shaped, with the camps on one side and military and civilian housing on the other. Nothing ever moves quickly; multiday waits, for unexplained security reasons, are standard. Ahmad and Wilson sometimes have to wait a week to see Omar for a few hours. To protect the Cuban iguana, in accordance with the Endangered Species Act, the speed limit on the base is set at twenty-five miles an hour — a good metaphor, Ahmad says, for the studied stalling techniques of the base’s administrators. The camps are on a level piece of ground close to the sea. They come into view when the visitors’ bus rounds the final curve. From that distance, in the beauty of the setting, the prison complex appears to be a resort.

Ahmad and Wilson are professors of law at American University, where they run the International Human Rights Law Clinic. Ahmad is slender and pensive; Wilson is a sizable guy whose default attitude is geniality. They began representing Omar Khadr after the U.S. Supreme Court granted due-process rights to Guantanamo prisoners in 2004. They took the case on legal principle but also, as Ahmad says, “to remind the world that this kid is there, that he is alive, that his life has value and meaning and that he’s been thrown in a hole. It’s our collective responsibility to treat him with the dignity that he deserves.”

When Ahmad saw Omar for the first time, in October 2004 — after the convoluted flight and the numberless delays and checkpoints and searches and phalanxes of armed soldiers, and after being told so many times how evil the detainees were — his first thought was “He’s just a little kid.” Omar was gaunt and pale, in a state of everlasting exhaustion, his senses starved by solitude. He had large gunshot-wound scars on his back and chest, and smaller scars over most of his body, several parts of which still held shrapnel.

“You feel a general protectiveness toward these folks just because they’re kept without access to anyone,” Ahmad says. “And because of Omar’s age and lack of world experience, you feel that much more protective. You’re conscious of not infantilizing him, but when someone is that young, you would be wrong not to recognize this. Our contention is that children are deserving of special protection — that’s been our legal approach, and it’s also been our ethos in our relationship with him.”

It took Omar a while to accept that his lawyers were not part of the interrogation system at Guantanamo. Their initial visits, Wilson says, were spent trying to get him to believe in them — legal strategy was secondary. Gradually, Omar revealed himself to be very shy and curious and, in most ways, still a child, with a child’s sweetness and credulous charm. Despite the rate at which his bones were lengthening, isolation and trauma seemed to have preserved him in emotional time. When he learned a new word — his experiences had left odd gaps in his knowledge — he tried to use it right away, and as often as possible. When Wilson and Ahmad offered to get him something to read, he asked for coloring books and car magazines and books with photographs of big animals. When they asked him what kind of juice he wanted them to bring back after a break during one meeting, he said, “Just something weird.”

Whenever Wilson or Ahmad left a pen on the interview table, Omar would pick it up and start taking it apart and putting it back together again. He always asked to play with Ahmad’s digital watch, which had a stopwatch function; he never tired of using it to test his reflexes. He wanted to know all about his lawyers: their ages, their hometowns, their family backgrounds, why they had chosen to become lawyers. The few short letters he was able to write are the work of a child:

To my dear family:- i miss you very much and i hope i can see you in the nearast time . . . don’t forgat me from you pray’urs and don’t forget to writ me and if ther any problem writ me. your [heart] son:- omar [heart] khadr

When he discussed the government’s case against him, Omar did not mention ideology or God. He was still devout, but he did not always manage to pray five times a day. He seemed to have drifted from the absolutism of his family.

Omar grasped legal concepts surprisingly quick. When Wilson and Ahmad half-seriously told him he should study law, he showed something close to delight. Then he laughed darkly: He was unable to contemplate a future so far removed from Guantanamo, a future in which an “enemy combatant” was acquitted and became a lawyer. On the advice of Wilson and Ahmad, he wrote a note to the presiding officer at his first military hearing in April, refusing to participate in the proceedings until he was removed from solitary confinement: “With my respect to you, i’m boycotting thes persedures untel i be treated humainly and fair.” ,p> Once Omar allowed himself to believe that he had acquired committed advocates, his life bent itself around his meetings with them. They had brought him back into the forward-moving world and reminded him who he was. His accounts of mistreatment emerged slowly. At the end of his first meeting with his lawyers, he mentioned, embarrassed, that he had been threatened with rape. He was convinced that Ahmad and Wilson would never return, and it suddenly occurred to him, during the interview’s final moments, that this might be his last chance to speak to the world. It was easier to reveal something shameful to confessors he would never see again.

It took several more meetings for the facts to emerge. Although the U.S. government denies mistreating Omar, neither Wilson nor Ahmad ever doubted the truth of what he told them. They had read hundreds of pages of detainee accounts of torture that independently corroborated one another. A Swedish detainee described being held for a dozen hours at extremely cold temperatures and senselessly moved from cell to cell throughout the night. An Australian detainee described the use of frigid and stifling temperatures, short shackles and random beatings. A Pentagon inquiry confirmed detainee accounts of torture by sexual humiliation. A former Guantanamo interrogator described detainees being “shackled for hours and left to soil themselves while exposed to blaring music or the insistent meowing of a cat-food commercial.” In an internal memo, an FBI agent described finding a detainee unconscious on the floor of a room “well over a hundred degrees . . . with a pile of hair next to him. He had apparently been literally pulling his own hair out throughout the night.” The U.S. Army’s own interrogation logs documented the treatment of a Saudi detainee who was interrogated in eighteen-hour sessions for forty-eight days, put on a leash and forced to bark like a dog, given intravenous fluids and locked in a room with no toilet, stripped and straddled and sexually derided by female guards, and subjected to a staged kidnapping that involved being tranquilized, blindfolded and flown to a fake destination.

There is no scientific evidence that such coercion is better than any other kind of interrogation; it is probably worse. SERE techniques were not designed to be used in the real world; they were designed to test the psychic endurance of Air Force pilots. When the FBI sent some of its best counterterrorism agents to Guantanamo soon after the camps opened, the agents chose to use what is known as rapport-based interrogation, which apparently worked. The FBI agents found the coercive tactics used by military intelligence both disgusting and stupid: The abusive treatment instantly destabilized detainees, making the information they provided unreliable as intelligence and useless in court.

By the time Omar’s lawyers took his case, it was clear that the torture methods used at Guantanamo had been directly authorized by President Bush. In January 2002, the president’s lawyer, Alberto Gonzales, working for the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, advised the president that nearly all forms of torture were legal. Physical abuse was not torture unless it generated the intensity of pain associated with “organ failure, impairment of bodily function or even death.” Psychological methods were illegal only if they inflicted harm that endured for “months, or even years.” Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld approved a new interrogation paradigm, and Gen. Geoffrey Miller instituted the same SERE techniques at Guantanamo that he would later bring to Abu Ghraib.

Rick Wilson and Muneer Ahmad have a lot of experience representing prisoners, mostly immigrant detainees and death-row inmates. “Nothing we’ve seen comes close to the experience of Guantanamo,” says Ahmad. “Not just the treatment of detainees but the brute force of state power.”

During the course of their research, the attorneys were struck by the overwhelming evidence that most of the detainees at Guantanamo are innocent. The CIA had pulled Abdurahman Khadr out of the camps not just because the detainees around him had become mentally unstable and uncommunicative, but because so few of them knew anything about Al Qaeda or the Taliban. During his debriefing, one of the first things Abdurahman told his CIA handlers was how utterly the United States had failed, in its military sweeps after the fall of the Taliban, to distinguish between the guilty and the innocent. In Afghanistan, the U.S. offered cash rewards for suspected Al Qaeda members that were sometimes equivalent to several years of local wages. The American military thus made every Arab-looking person in Afghanistan vulnerable to opportunists. Warlords rounded up people and brought them en masse to American authorities. Others were turned in to settle grudges, or because they had once associated with someone from Al Qaeda. U.S. intelligence apparently took criminals and mercenaries and underpaid soldiers at their word.

In his debriefing, Abdurahman Khadr told the CIA that only ten percent of the detainees at Guantanamo “are really dangerous.” The rest, he said, “are people that don’t have anything to do with it, don’t even . . . understand what they’re doing here.” One innocent man, Abdurahman said, was given up by his own son for $5,000. Another detainee was nothing more than a drug user: Every time the MPs came around, he begged them for hashish: “He doesn’t even know what he’s doing here,” Abdurahman said. “Truly a drug addict, not Al Qaeda at all.”

One military-intelligence officer, speaking anonymously, told a reporter that more than seventy-five percent of the detainees at Guantanamo are innocent. When the government recently prepared Summaries of Evidence for its 517 detainees in an attempt to justify its “enemy combatant” designation, only eight percent were “definitively identified” as Al Qaeda fighters. Sixty-six percent have no definitive connection to Al Qaeda at all. The detention camps of Guantanamo Bay are filled with shepherds, taxi drivers, farmers, small businessmen, drug addicts, homeless people and children.

For Rick Wilson and Muneer Ahmad, this nasty truth led to an unnerving conclusion: After the invasion of Afghanistan, the Bush administration effectively kidnapped hundreds of innocent people because they looked like Arabs and shipped them to a detention facility designed to torture them nonstop and in perpetuity. If the president were tried in the Hague, the prosecution would have an easy case.

Before the Supreme Court extended the protection of the Geneva Convention to Guantanamo detainees, the government charged Omar Khadr with murder, attempted murder, conspiracy and aiding the enemy. The allegations were odd: Khadr was a soldier fighting in support of a national army. The Geneva Convention sensibly prohibits any government from charging enemy soldiers with murder for acting like soldiers. It is hard to say how the government will now reformulate its charges; it is hard to say how long Congress and the administration will spend designing tribunals that satisfy the Supreme Court. For the moment, however, Omar Khadr remains an enemy combatant and, therefore, subject to unlimited solitary confinement.

Ahmad and Wilson have filed motions in federal court seeking to enjoin the continuing torture and inhumane confinement of their client. Thus far, none has been granted. Except for a brief hiatus, Omar Khadr has been alone in a cell at Guantanamo Bay for close to four years. Four years is nearly a quarter of his life. Since he was caught, he has grown eight inches. It is nearly impossible for him to believe that he will ever be released, and his daily life remains filled with menace: He is so conditioned to abuse in captivity that he is incapable of believing he will ever be free of it.

A year and a half ago, Dr. Eric Trupin predicted that Omar Khadr would suffer serious permanent damage unless he was immediately moved into a humane detention facility, convinced that he was safe from all injury and provided with acute psychological care. Such a course of treatment, if ever administered, will come several years too late. It is possible that Omar’s mental life will progressively fracture into suicide attempts, hallucinations and paranoia. Having lived out the final years of his adolescence in Guantanamo Bay, he has learned nothing about the conventions of adult life, but he has as deep an understanding of powerlessness as any person can.

In the summer of 2005, Omar joined 200 other detainees in a hunger strike. They were protesting their unlimited detention without due process. Within a few weeks, guards began to beat them and force-feed them through the nose with thick tubes. From the diary of Omar Deghayes, a detainee who participated in the strike: Omar Khadr is very sick in our block. He is throwing [up] blood. They gave him cyrum [serum] when they found him on the floor in his cell. Omar was carried to the hospital. As he was being moved back to his cell, he collapsed. The guards beat him.

The resolve of the strikers deteriorated, and the strike ended. No concessions were made.