Op-ed by Omar Khadr, Bowden Prison Canada | 2014 10 28

Ten years ago the Canadian government established a judicial inquiry into the case of Maher Arar. That inquiry, over the course of more than two years of ground-breaking work, examined how Canada’s post-Sept. 11 security practices led to serious human rights violations, including torture.

Ten years ago the Canadian government established a judicial inquiry into the case of Maher Arar. That inquiry, over the course of more than two years of ground-breaking work, examined how Canada’s post-Sept. 11 security practices led to serious human rights violations, including torture.

At that same time, 10 years ago and far away from a Canadian hearing room, I was mired in a nightmare of injustice, insidiously linked to national security. I have not yet escaped from that nightmare.

As Canada once again grapples with concerns about terrorism, my experience stands as a cautionary reminder. Security laws and practices that are excessive, misguided or tainted by prejudice can have a devastating human toll.

A conference Wednesday in Ottawa, convened by Amnesty International, the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group and the University of Ottawa, will reflect on these past 10 years of national security and human rights. I will be watching, hoping that an avenue opens to leave my decade of injustice behind.

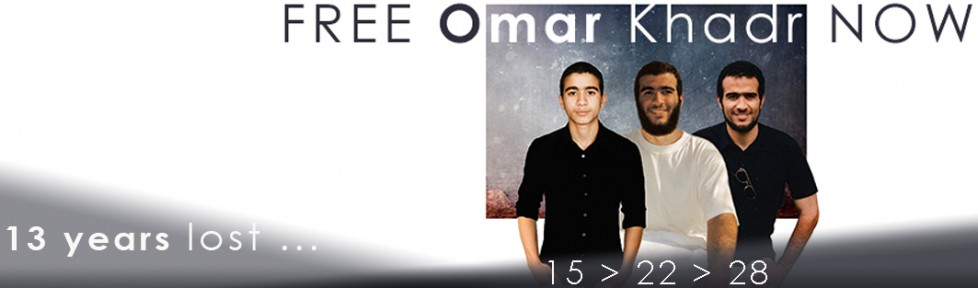

I was apprehended by U.S. forces during a firefight in Afghanistan in July 2002. I was only 15 years old at the time, propelled into the middle of armed conflict I did not understand or want. I was detained first at the notorious U.S. air base at Bagram, Afghanistan; and then I was imprisoned at Guantánamo Bay for close to 10 years. I have now been held in Canadian jails for the past two years.

From the very beginning, to this day, I have never been accorded the protection I deserve as a child soldier. And I have been through so many other human rights violations. I was held for years without being charged. I have been tortured and ill-treated. I have suffered through harsh prison conditions. And I went through an unfair trial process that sometimes felt like it would never end.

I am now halfway through serving an eight-year prison sentence imposed by a Guantánamo military commission; a process that has been decried as deeply unfair by UN human rights experts. That sentence is part of a plea deal I accepted in 2010.

Remarkably, the Supreme Court of Canada has decided in my favour on two separate occasions; unanimously both times. Over the years, in fact, I have turned to Canadian courts on many occasions, and they have almost always sided with me. That includes the Federal Court, the Federal Court of Appeal and the Alberta Court of Appeal.

In its second judgement, the Supreme Court found that Canadian officials violated the Charter of Rights when they interrogated me at Guantánamo Bay, knowing that I had been subjected to debilitating sleep deprivation through the notorious ‘frequent flyer’ program. The Court concluded that to interrogate a youth in those circumstances, without legal counsel, “offended the most basic Canadian standards about the treatment of detained youth suspects.” That ruling was almost five years ago.

I had assumed that a forceful Supreme Court ruling, coming on top of an earlier Supreme Court win, would guarantee justice. Quite the contrary, it seemed to only unleash more injustice.

Rather than remedy the violation, the government delayed my return from Guantánamo to Canada for a year and aggressively opposed my request not to be held in a maximum security prison. It is appealing a recent Alberta Court of Appeal decision that I should be dealt with as a juvenile under the International Transfer of Offenders Act.

No matter how convincingly and frequently Canadian courts side with me, the government remains determined to deny me my rights.

I will not give up. I have a fundamental right to redress for what I have experienced.

But this isn’t just about me. I want accountability to ensure others will be spared the torment I have been through; and the suffering I continue to endure.

I hope that my experience – of 10 years ago and today – will be kept in mind as the government, Parliament and Canadians weigh new measures designed to boost national security. Canadians cannot settle for the easy rhetoric of affirming that human rights and civil liberties matter. There must be concrete action to ensure that rights are protected in our approach to national security.

National security laws and policies must live up to our national and international human rights obligations. I have come to realize how precious those obligations are.

That is particularly important when it comes to complicity in torture, which is unconditionally banned.

I have also seen how much of a gap there is in Canada when it comes to meaningful oversight of national security activities, to prevent violations.

And I certainly appreciate the importance of there being justice and accountability when violations occur.

I want to trust that the response to last week’s attacks will not once again leave human rights behind. Solid proof of that intention would be for the government to, at a minimum, end and redress the violations I have endured.

Originally published: Khadr: Misguided security laws take a human toll by Omar Khadr, Ottawa Citizen | 2014 10 28

Written in the context of the event: Arar +10: National Security and Human Rights a Decade Later | 2014 10 29